Just Passing the Time

fighting back by living in the world itself

Growing up, family dinner at Grandma and Grandpa’s was a regular affair. The paternal side of my family—a small, jovial bunch—would gather at the house on the hill for a quintessential meal: lasagna, salad, and bread. That was how I earned the nickname “Bread Boy,” throwing back slice after slice like “dessert” was spelled G-L-U-T-E-N.

As dinner was prepared, my sister and I would challenge Grandpa to checkers or an ambitious game of Monopoly. After we’d polished our plates, the adults played Hearts as I sat on a relative’s lap and “helped” sort their hand. On a calmer, quieter night we might play Rummy. I remember the feeling of warmth in those moments, all of us gathered around the circular dining table, of something I couldn’t yet articulate. The drinks, the banter, the pleasant ignorance of the internet age to come. Like clergy gathered around the sacrament, we ritualized coming together through games.

I also remember the irksome desire to be older, to reach the arbitrary age where I could hold and sort my own cards, to understand this game which, to me, signified maturity. Like a rite of passage forthcoming, the size and dexterity of my hands indicating I was not yet ready. Overtaken by frustration or impatience, I’d crawl below the table, putting my child-sized hands to use and stealthily tying together Grandpa’s brown leather shoes. Or I’d excuse myself entirely, out to the living room, to my own game fit for a certain childlike imagination.

Grandma kept an immaculate house: White couches on white carpet, a glossy, black baby grand piano in the corner. Ornate wooden end tables capped off the edges of the living room. Inside one of the end tables, a community of dice lay in wait for their gamemaster. There were dozens of them, all shapes and sizes and colors, relics of casinos haunted and board games disassembled. I stacked them, talked to them, rolled them indiscriminately—numbers be damned, there’s no right way to use a die. When Grandma and Grandpa downsized to a single-level, among the many items up for grabs were those dice and Grandpa’s game boards. I took possession of them all, lugging them through the life of my 20s, holding on to something without knowing what.

In my early-twenties I developed a belated affinity for the game of Yahtzee. Mom and Dad first taught me as a kid, playing on camping trips throughout the Pacific Northwest, but post-college our social group unwittingly let loose its community-building potential. We all played a role: one would stoke the music vibes, one or two might cook up some chicken wings, and the rest stood on “Yaht alert!” This vital responsibility entailed a thunderous drumroll anytime someone was one dice away from five-of-a-kind.

Yahtzee silently boasts an inherent unseriousness, a nonsense that adds to, or perhaps creates, its air of intimacy. If you play it right nobody cares who wins, everyone simply rooting for the elusive Yahtzee to materialize so we can all exclaim a made up word. In letting go of the outcome-oriented, one holds onto the moment; through the collective comes something greater than the roll of five dice.

I took this affinity and a set of dice across the world to New Zealand, where a friendship with a quippy UK boy named Sam was built upon footy and whether or not to take a Full House so early in the game. The two of us hiked four days on the Abel Tasman Coast Track, parsing apart stretches of walking with peanut butter sandwiches and Long Straights, playing into the night by candlelight. Seven years later my partner and I traveled overseas to visit Sam and his partner Sophie, the four of us bonding as we Yahtzeed on the floor of their modest flat, the contralto vocals of London Grammar filling in the spaces around us.

Attention is a fashionable word these days. After all, we live in an Attention Economy, a system in which we “pay” not only with our dollars but with our time, focus, and energy. The owners of this economy—Musk, Zuckerberg, Bezos, among others—are the same henchmen flocking to President Trump, sitting behind him at the inauguration and, in the case of Musk, haphazardly conducting more than enough of Trump’s presidency for us to be concerned. MAGA, a conservative political movement at least theoretically built on respect for the working class, cozying up with literally the richest men in the world. Their money is astounding, their attentional influence unfathomable.

For more than a decade I’ve persistently observed my own inability to moderate the use of algorithmic platforms. The social medias I subscribe to have dwindled and, in general, the direction of my attention has trended in a positive direction. Yet I routinely circumvent my own self-imposed restrictions. Deleted apps from my phone: access them through a web browser. Logged out of Facebook and changed the password: access reals on YouTube. And if I’m having a bad day? Forget it, I deserve this mindless time to wind down.

I use the Minimalist Phone app, basically a black screen and text-based list of downloaded apps “designed to reduce your brain’s dopamine addiction” while adding mindfulness and control back into the human-phone relationship. And here I am, still expressing my attentional discontent.

The bright side: I’ve stopped punishing myself for it. As the insidious design of these platforms increasingly comes to the light—their profound ability to prey on our neurochemical weaknesses—I ask myself: can we, the users, really be at fault? Sure, blame the environment we each create—the apps, notifications, and display settings—but not the mythical “decisions of willpower” we make in each moment. Control of our reward pathways has been handed over, and with it our experiential selves.

I routinely question if the drastic step of going full “dumbphone” would be a net positive on my life. Music, podcasts, Maps, photos, notes—these functions all enrich my life (particularly while out of the house) in ways that would feel unnecessarily cumbersome to replace with an iPod, paper maps, camera, and pen and paper. The key to any technology is determining where it serves us and where it doesn’t. This point in time illustrates the challenge of reducing the use of algorithmic technology—and to some extent the internet in general—while they become increasingly enmeshed in all aspects of our lives, macro forces doing everything in their power to encourage their use.

The docudrama The Social Network came out in 2020, and even then founders and CEOs of various tech & social media companies acknowledged the manipulative design of their platforms, admitting they didn’t let their own children use them. Jonathan Haidt has spent years valiantly uncovering the detrimental effects of social media—both in his books and Substack After Babel—as have many others.

This Attention Economy—seemingly born out of capitalism’s intrinsic incentive toward unchecked innovation, growth, profit, and greed—is like an “algorithmic cage divorced from reality,” Adam Serwer writes. The private companies in charge possess “an unprecedented ability to manipulate and control the populace…..It does not matter to them if what they are showing people is real or factual; what matters is that no one stops scrolling. The goal is to keep Americans in that cage. The purpose of this cage is to make companies a profit, but we are now entering an era when the government is pressuring them to keep Americans docile, obedient, controlled, and, in some cases, hopeless, ‘spinning on an endless hamster wheel of reactive anger,’ as the journalist Janus Rose put it.”

One goal of Attention Economics and its political affiliate, as Rose articulates, is “not to persuade, but to overwhelm and paralyze our capacity to act.” Mainstream media coverage barrages us with negative, hopeless content to the point of apathy or some other emotional outlet, too often something consumption- or entertainment-based. A convenient recipe for certain purposes, this is not the recipe for an engaged, civically-minded population. An engaged citizen is not aware of—cannot be aware of!—each and every current event, but rather cultivates a select inventory of concerns and acts on them. If isolated inaction led us into this situation of polarization and democratic crisis, collective action in the world may lead us out of it.

“Under this status quo, everything becomes a myopic contest of who can best exploit peoples’ anxieties to command their attention and energy. If we don’t learn how to extract ourselves from this loop, none of the information we gain will manifest as tangible action—and the people in charge prefer it that way.”

—Janus Rose, “You Can’t Post Your Way Out of Fascism”

A few weeks ago some friends and I checked out a much talked about smash burger spot—just a guy and some buddies in an alley, smashing meat into a few Blackstone grills. Expecting a wait, I bundled up, brewed a thermos of tea, and packed my portable Yahtzee set. We quickly made friends with the gregarious woman in line behind us, asked her to join our game. The burgers were solid enough, for an hour-plus wait, but the experience in line, playing a game just to pass the time, was the highlight of the night.

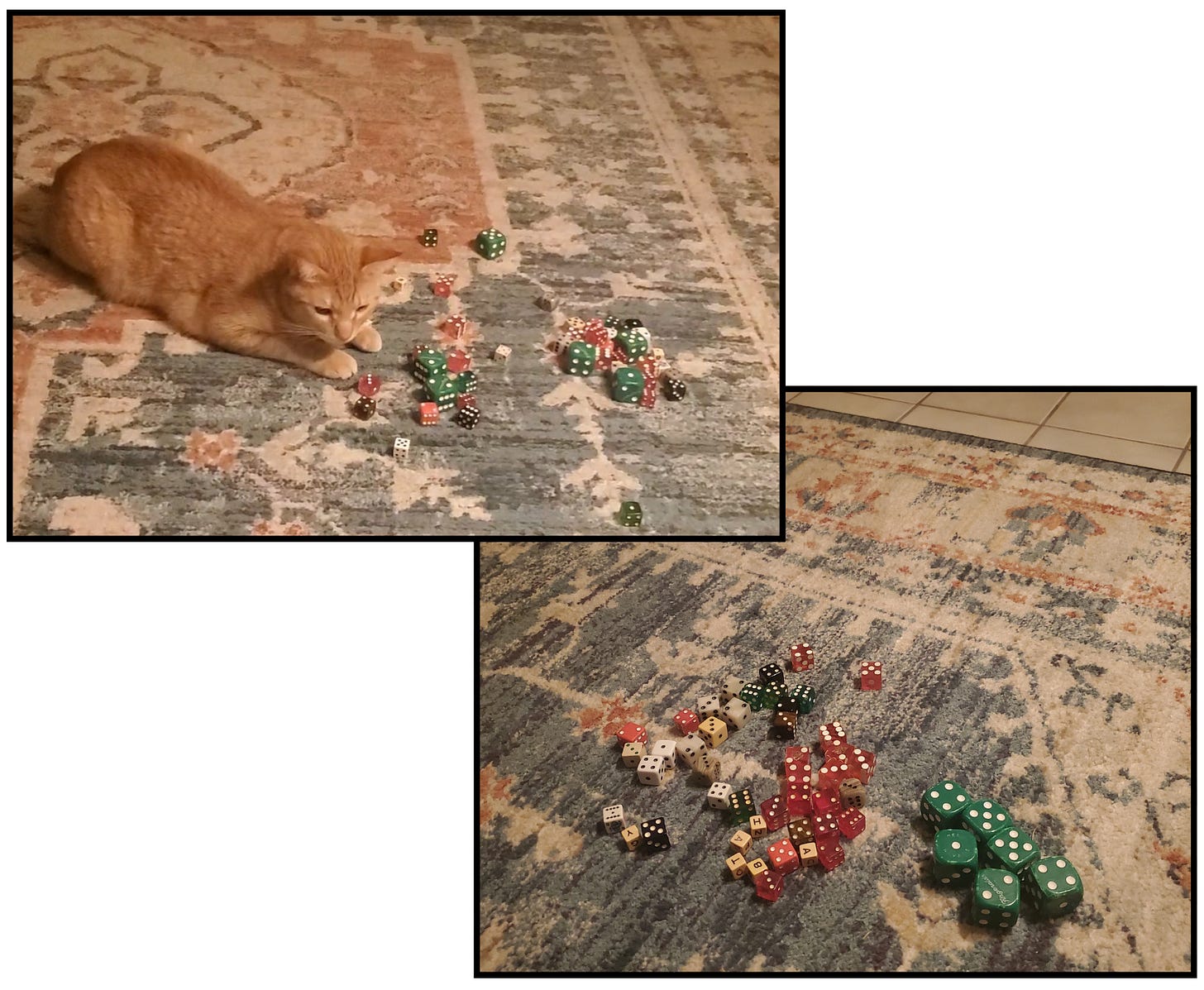

A week later I brought out the entire collection of dice, leisurely yet deliberately inspecting them like I might have done as a child. Placing myself back in that space and time, back in the house on the hill, I noticed details in this strange amalgamation as if laying eyes on them for the first time. Most dice had the normal dotted pips, but some were marked with letters and some with royal depictions of face cards. I sat in the curiosity of what games these might have belonged to and then just as quickly let the thought go.

Just before this I’d watched a documentary about Brian Eno, now feeling encouraged to look at ordinary objects from a novel perspective. So I ended up playing Yahtzee with my cat. I beat him by one point.

This essay is about attention and the ways powerful corporations take it away from us, but it’s also about living in the world itself. Algorithms make up more than just social media; they control Netflix streaming suggestions, internet advertisements, and the mail sent to our front door. Every time we’re online, we sharpen our internet persona. This persona is then bought, sold, and traded in order to further capture our money, attention, and, in a very real sense, our lives.

I won’t go so far as to boldly claim that using the internet in any capacity is akin to actively taking part in one’s own experiential capture—the internet is ubiquitous and increasingly unavoidable. We all need grace. Yet I believe we collectively know enough to support the claim that the unexamined life online is barely a life at all. Quality time with friends and family—whether that’s playing cards, board games, or anything else sans screen—may not change the world. But then again, maybe it will. It is in these experiences of person-to-person exchange that beliefs are shared, ideas are altered or reinforced, and movements are formed. I recognize I am placing an inherent value on analog lived experience, a value I am willing to defend.

Rejecting these addictive platforms will force us into new relationships with ourselves and the nature of time. Life will pass more slowly, as we reacquaint ourselves with boredom and downtime and awareness of what’s in front of us. The immediate dopamine hits we’re accustomed to will subside, replaced with something intentional and sustainable. These are challenging realities we’ll face individually, but we can each build momentum from the presence of others.

I’m a novice in my own journey, still feeling like I fail as often as I succeed in living in the world itself. But I will continue to roll the dice, taking my chances that consciously focusing my attention will bring clarity and peace in a world of distraction.

Really love this piece Kyle. And yes, dessert is spelled GLUTEN! You know I listen to a lot of Ezra Klein and I've really liked a number of his episodes about attention. I love how powerful the simple family game nights were to your family--and continue to be to you and your community. Keep writing! Thanks.