In the season finale of The Office, the sitcom that came to define the late 2000s and early 2010s, the character Andy Bernard, on the verge of tears, gives his most famous, lasting line:

“I wish there was a way to know you’re in the good old days before you’ve actually left them.”

How can we answer this question? To recognize and ponder this stark reality is one thing, yet to consciously embrace it in the presence of the group—the very people who make up the good old days—is to be somewhat pulled out of the present moment we’re all told we should embody. If something is coming to an end, should we want to know about it? Is ignorance really bliss? Or would a sort of bittersweet awareness better suit us, both in the present and in memory?

…these feel like questions better suited for the Little Philosophers.

Humble Beginnings

Arising from a common desire to share books, articles, movies, etc. and talk about them in a thoughtful, organized way, the Little Philosophers originated in early 2024. The oldest record I have of its existence is an email from Hunter

titled “Community through Conversation,” thanking four of us for gathering at his apartment and discussing simple, straightforward questions such as: How did we get into our current societal predicament? and Can we imagine a humanity that has the wisdom to steward its own technological power reasonably well? I remember the group making little headway, constantly bogged down by pesky questions of definition and subjective perspective. To philosophize and question the world, however amateurly one goes about it—and one should go about it—requires common groundwork, expectations, and group norms. We were finding our way.Into the spring season the group was still budding, like an early flower insecure in its place. What might be considered the first official Little Philosophers gathering—perhaps the day we came up with our endearing nickname “Little Ps”—took place in April, a pad thai dinner preceding a conversation about the question: If you reach a strong moral or ethical conclusion about an issue, do you have a personal obligation to become politically engaged in the support or opposition of the issue? Learning from past efforts, the stage was wisely set with a shared definition of politics as “the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status.” For a few hours we fluttered in and out of the topic itself, but upon leaving there was an unquestionable sense that something unique was forming.

In May, we looked inward, contemplating the private questions of: How does one know they are living into the person they want to become? What does it feel like and/or what are you doing when you feel like you're embodying the version of yourself you want to be? As the host for this dinner, I felt an intense appreciation as I looked around our extended table—everyone savoring the food farmed by friends of ours, prepared by Kenzie & I’s own hands—astounded by the pace in which we can come to cherish people in our lives. In a matter of months this group had established itself—some lifelong friendships but mostly newer connections—and bloomed into a committed core of about a dozen, the most dynamic, meaningful social group I’ve ever been a part of.

Highlights and Moments to Learn

The most memorable Little Ps gathering that I recall came in the dog days of summer, as Anna prepared a delicious dinner in her third floor apartment….on the hottest day of the year….with the A/C out of order. We attempted to discuss personal intentions and authenticity, but all I remember is the hysterical lethargy, the absurd humor in why we continued to endure the sweltering heat, sweat dripping onto our empty plates. Even Anna’s roommate fled, seeking cooler climates. Then someone mentioned ice cream, and then the river, and we were out, spontaneously moving the discussion to a standing circle in the shallows of the Boise River. Once there, the conversation flowed effortlessly into the sunset, in sync with the cool, refreshing water.

Another notable event came in the midst of what felt like a fruitful discussion about the touchy subject of money. The prompt was: How does your philosophy of money impact your generosity? With typical deadpan delivery, Tanner took his opportunity to speak to express his boredom and dissatisfaction with what felt like a severe deviation from the prompt. We’d previously discussed how we might navigate disagreement and conflict, but this was our first true exercise in what is always easier said than done.

And perhaps my favorite gathering was our Italian-themed Friendsgiving, gratitude and thankfulness the obvious topics of discussion on this night. With roughly one bottle of wine per person and shots of limoncello for good measure, safe to say things got loose. Passersby were brought in off the street, fed heaping plates of lasagna and ratatouille (someone missed the Italian memo), and thrust into theological dialogues. I love this group for its boisterous, anything-goes approach to life, a free-spirited mentality of which my cautious, overthinking personality can always use more.

The last gathering the comes to mind was Brooke & Brannic’s first time hosting, serving up their famous wood-fired pizza with the iconic cream cheese dollop. The evening’s discussion stemmed from an article in The Atlantic titled “The Anti-Social Century,” commenting on the loneliness epidemic and how increasing time spent alone may alter our experience of reality. The conversation prompt was: Why do you think loneliness has become so prevalent? What is a potential antidote to this loneliness epidemic? The irony was not lost on us, a group of close friends so far removed from the unfortunate fact that one in two American adults experiences loneliness. We, on the other hand, have a hard time keeping a weeknight void of social plans. In the back of my head I wondered, should we even be discussing this topic?

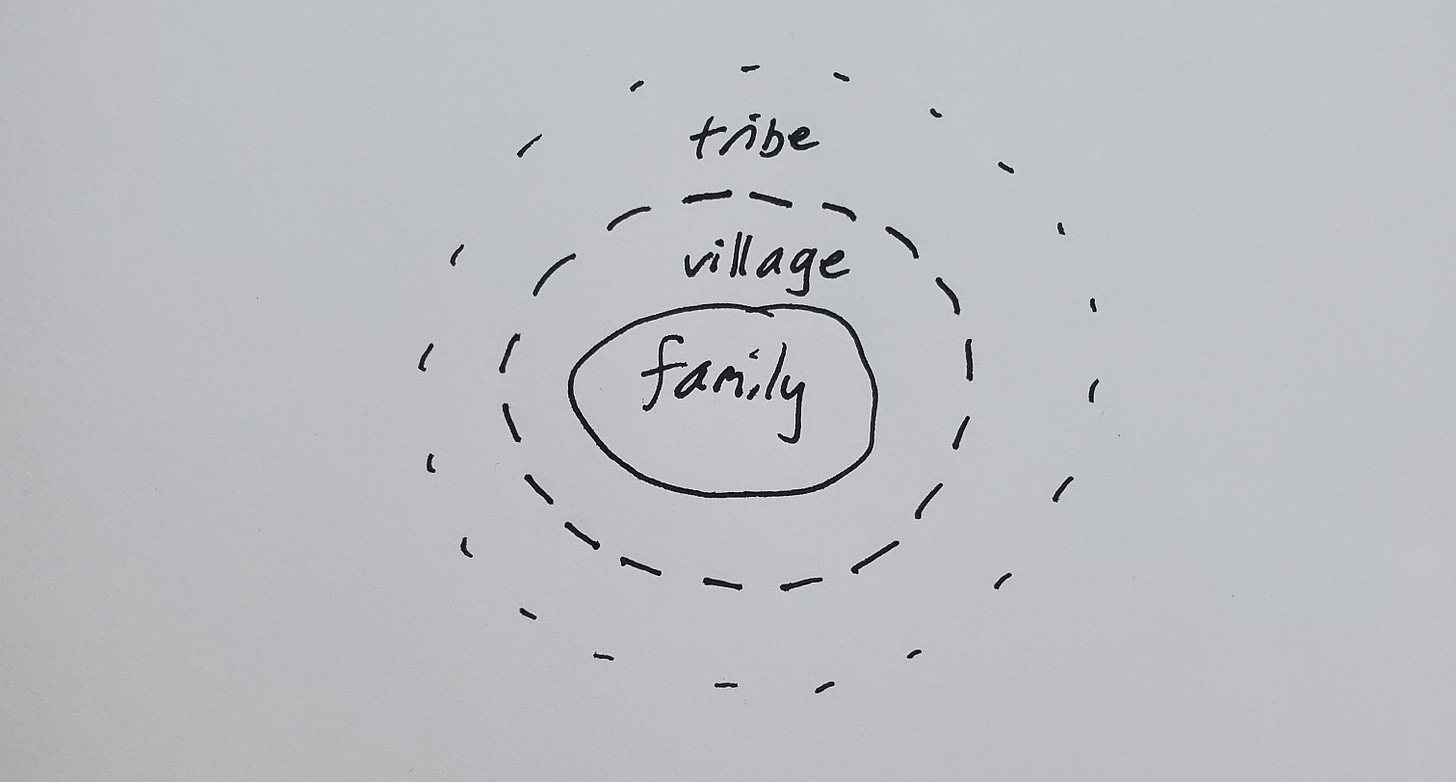

If you imagine society as concentric rings, beginning with “family” in the center, then the “village,” and our extended “tribe” as the outer ring, it is the middle level of the village that the internet, social medias, and political polarization have eroded most. Interactions with village members, the strangers we used to interact with at coffee shops or grocery stores, have been replaced by screens and fearful silence. But an engaged community member, comfortable with meeting new people and communicating on a range of topics, can so easily become a friend and source of connection to someone experiencing loneliness. I’m far more outgoing today than a year or two ago—I hope touching the lives of strangers on a regular basis—in large part due to the openness and acceptance of the closest people in my life.

The lives of the Little Philosophers have their own ebbs and flows, and we’ve never tried to force these gatherings given the prevailing currents. Instead we’ve followed an organic process, trusting that if a few weeks had passed, or someone felt moved by a reading or the urge to host, an invitation would be sent out and a critical mass would attend. I believe this fluidity has been a strength of ours.

In just over a year’s time, what’s resulted is a profoundly meaningful avenue of learning about other people and what it means to live in community. We’ve learned that community itself isn’t a rose-colored utopia where everyone agrees, but an ethereal, collective phenomenon granting care and respect and tolerance to others, regardless of background or beliefs. We’ve come to experience first-hand how strongly childhood, environment, and trauma shape our thoughts and worldview. And we’ve learned that life is difficult, and to share our intimate sufferings and hardships with others is perhaps at the root of the human experience.

And while I say we learned all this, as if for the first time, it might be more apt to say that through intentional gathering and dialogue we were reminded of these fundamental truths. This recognition sends me back to my November 15th essay, in which I argued that ‘the only way out [of our social disconnection and polarization] is through’. Through the avoidance of social medias and other thought-distorting mediums; through real life interaction with friends and strangers alike; through intimate questions and honest responses. My last essay “Just Passing the Time” touched on themes of algorithmic platforms and the capture of human attention and thought, pulling us away from living in the world itself. But impassioned, persuasive appeals for a certain way of living call for examples, to show that ideas presented are not just idyllic fantasies but realities which could—are actually—occurring in the world. The story of the Little Philosophers is an example.

You might be thinking, “This isn’t real community engagement. What impact are you really making in the world?” Such a critique is completely fair to raise. It’s easy—and to some extent, dangerous—to remain in the comfortable space of heady, philosophical conversation, and much more difficult to put yourself out there and act in the world.

But how can we expect to meaningfully influence the world if we can’t first respectfully and productively disagree with our family, friends, and immediate peers? The Lil Ps may be a tight-knit social circle with great overlap, but there is also a great deal where we differ among topics of life background, religion, and how we should aim to structure our social, political, and economic institutions. We see these differences as opportunities to dig in, challenge one another lovingly, and learn about ourselves in the process. At the very least, we are gathering intentionally, breaking bread, and sharing about our lives, and I believe there is a very real good in such a practice.

All We Can Be Sure of Is Change

Thus brings us to “the good old days.” The Little Philosophers will never end, but the near horizon will bring significant change. One of us will head back to the forests for another fire season, one will move overseas for grad school, and one into the sacred life of marriage and motherhood. Yet, none of us will experience stasis. We have PhD classes and dissertations to complete, LMSW hours to satisfy, career changes to contemplate, non-profits to operate, mountains to summit and ultras to run, laughs to bring about, and books to write.

As we increasingly come to recognize and value the profundity of the last year’s relationships, communication, and growth, should we pause to observe the blessed moment we’re holding? Or have we known it all along?

I believe we create the good old days by reaching for life, by being vulnerable and open to experience. Sometimes the universe answers the call, responding in the form of other humans craving the same depth and vitality out of life. Or maybe those people enter your life with the purpose of teaching you how to crave it more than you ever thought was possible, how to laugh and speak without self-consciousness, how to dance like nobody’s watching.

The good old days don’t take place in isolation; they’re always spoken of in retrospect, in the company of others. But the good old days implies a time of normalcy, or perhaps just a different sort of shimmer. Maybe a new magic quickly returns, this time looking slightly different. Maybe there is an extended lull, so to speak. Not in any pejorative sense, but one that signifies efforts and intentions focused inward.

By learning to observe how we cultivate the good old days, we come to recognize when we’re living them. This is the reflection of life—not to act different in any way, just to appreciate, to be grateful. To give another hug when you might not otherwise; to say how you really feel even when it’s hard to get the words out.

The one thing we’re always guaranteed in life is change. Taoists embrace this constant state of flux, coming into harmony with change and through it finding a sense of stillness and peace. For the development of my own life, I welcome this change—this one particular wave in a sea of constant unpredictability—my sights set on new outputs of energy.

Balance—polarity—gives us the good old days.